How to forgive lies

Péter Vida, professor at Corvinus University of Budapest, and his colleague Alessandro Ispano, researcher at CY Cergy Paris Université, have developed a mathematical model that, when applied to interrogation situations, avoids that the suspect receives the most severe punishment – which is in the interest of neither the interrogator nor the suspect – and thus allows the most effective differentiation between the potentially innocent and the guilty. Their study was accepted in the Review of Economic Studies, one of the top five economic journals in the world, on 7 January.

“The model is designed for interrogation situations in the justice system, but it can be applied to any situation where someone is being questioned. For example, when a parent asks his (or her) child about the time spent playing video games, or the boss asks his (or her) employee in home office about the amount of time spent on work”, explains the Corvinus researcher.

Game theory in the interrogation room: using the most severe punishment is not efficient

In an ideal world, justice would find and punish the guilty and acquit the innocent. But in reality, the interrogator inevitably makes mistakes: accuses the innocent and lets the guilty go. Péter Vida and his Italian colleague have developed a game theoretical model with asymmetric information on both sides, in which the interrogator makes as few mistakes as possible.

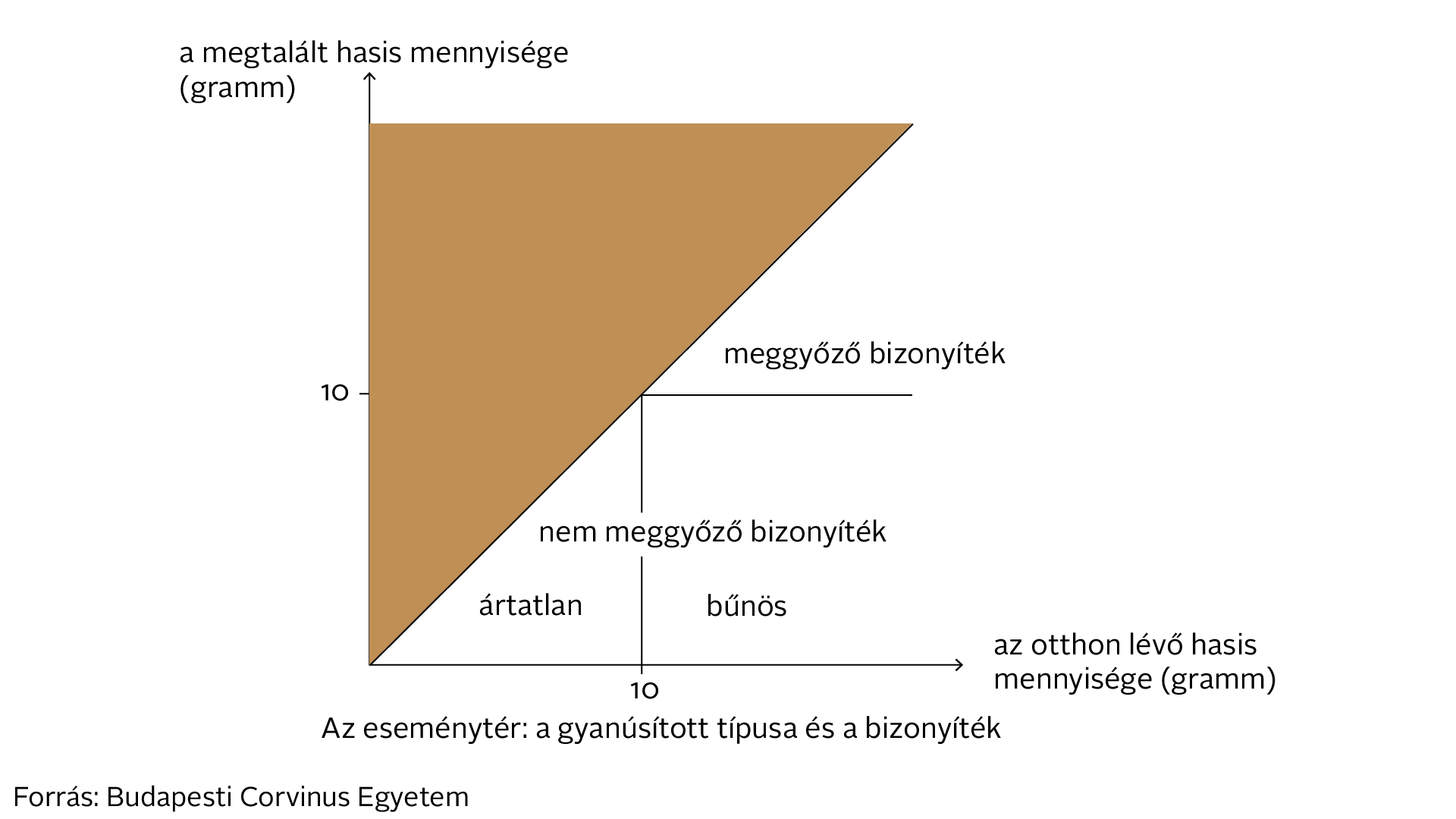

The key finding of the researchers’ study is that some recanted lies should be forgiven because the most severe punishment is inefficient. For example, consider a drug dealer who keeps various amounts of hashish in his apartment. Let’s assume that the legal limit for personal use in a given country is 10 grams. There are days when he has more and days when he has less. The police search his home on a random day and take him into custody. The dealer knows how many grams of hashish he had in his apartment that day, but he does not know how much of it the police found. This is the starting point for the interrogation.

What happens if a police officer asks the suspect about the amount of hashish in his home and based on his answer immediately decides whether he thinks he is guilty or innocent? It appears that this method of questioning is inefficient because those caught lying must be severely punished immediately. If, however, the interrogation continues with the police officer presenting the suspect with convincing evidence – if he has it – the liars will recant their lies and confess. In this case, the police officer should not severely punish some of the lies that he has caught but which have been recanted. On the contrary, it is worth a lighter penalty in exchange for these confessions. In this way, the most severe punishment can be avoided, which is in fact only ever present as a threatening tool during the interrogation. In fact, by doing so, the interrogator makes only the minimum number of mistakes and is therefore as likely as possible to identify the culprit correctly.

Police bluffing comes at a price; the “right to remain silent” principle can also benefit the interrogator

The difficulty of the model lies in the asymmetric information on both sides, which is gradually and only partially resolved in a dialogue that faithfully reflects reality. For example, an interrogation is different if the officer can exaggerate the strength of his evidence (bluff). In this case, the guilty party will not recant his lie because he discounts the truthfulness of the bluff. The model can also be used to examine different variations: for example, the two researchers also looked at how different countries’ jurisprudence influences the outcome of an interrogation. Interestingly, for example, their results show that the right to silence principle in US case law can ultimately benefit the interrogator.

Péter Vida and Alessandro Ispano’s model was the result of five years of scientific work. The theory will soon be tested in an experiment with humans to prove how it works in real-life situations.

“We hope that we have succeeded in creating a model that will serve as a reference for further developed game theoretical models by other researchers in the future,” adds Péter Vida, professor at Corvinus and CY Cergy Paris Université.