Bhutan and Gross National Happiness

You are a second year PhD student at Corvinus, one of your supervisors is Professor László Zsolnai and apparently, you have “fallen in love” with Bhutan. How did you become interested in this Asian country half the size of Hungary?

I used to work for Levi’s, I was involved in corporate responsibility. During my work in London, I happened to meet a Bhutanese woman who, together wit her husband, turned out to have established the Loden Foundation which used to be supported by the current King of Bhutan when he was still Crown Prince. My interest in this small country, which has long been very isolated, was awakened. I first visited in 2011, and it was my interest in sustainable development, Gross National Happiness and Buddhism that first took me there. I had planned to come home after a few months of volunteering. My first trip was followed by fifteen others.

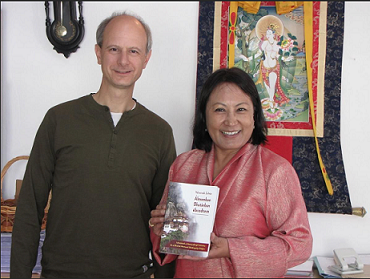

Zoltán Valcsicsák with Dago Beda, head of one of the oldest travel agencies in Bhutan (Photo by Thinley Wangcuk)

You have also written a book about this country, “In my dreams, I woke up in Bhutan”. Professor László Zsolnai, Head of the Corvinus Centre for Business Ethics, wrote: “The author presents and analyses in detail a conceptual framework of gross national happiness that boldly breaks with the one-sided idea and practice of economic growth driven by Western materialism and individualism.” What does Gross National Happiness really mean and how is it measured?

GDP is, of course, an important measure in the life of any country, but it is not the only measure and it is not enough. It is obviously a good thing when a country builds a new road or makes an important investment, but how these developments contribute to people’s well-being is equally crucial. There are many happiness indices in the world, but they all imply different things. In Bhutan, just last year, they conducted a survey – they do it every five years – and they had surveyors going around the country, reaching every small village, asking people how satisfied they were with their standard of living, their health, their education, whether they got enough sleep, about their mental state, and how satisfied they were with their leaders – local and national. This is used to calculate the country’s happiness index using sophisticated statistical methods. These considerations, as well as the ecological footprint and social impact of each activity, for example, are taken into account by the government in all its decisions.

Superman slips off the gho (traditional Bhutanese male attire) (photo by Zoltán Valcsicsák)

So what exactly does the happiness index mean? You hear a lot about how people in Europe are happiest in the Nordic countries, especially Denmark.

The Bhutanese survey shows that the majority of people in the country are happy, but that means something different there than in Europe. In European countries, it’s usually about individual happiness, “if I’m happy, maybe my family is happy, that’s very good”, whereas in Asia it’s more about the harmony, contentment and serenity of the wider community, a serious aspect of “let’s look after everyone, I can’t be so happy if others aren’t”. All this implies a kind of inner balance, calmness, and is strongly linked to Buddhism. The important question is how a society can create conditions where the majority are physically and mentally healthy.

As the founding president of the Hungary-Bhutan Friendship Society, you also organise trips to this small Asian country of 780,000 people. What would you like to show Hungarian tourists there?

Besides the country’s natural beauty, unique culture and rare human values, there is perhaps no other place in the world that has developed as much as Bhutan. In the 1950s it was a closed feudal kingdom, today it is an open constitutional monarchy. It is perhaps the last country in the world (in 1999) to introduce cable TV and internet, and yet today almost everyone has a mobile phone and therefore internet. In the 1950s, more than 80 percent of the population was illiterate, but today public education is free and children learn English. Many of them go to university, even the children of illiterate peasant parents – of course, this creates new problems, as there are too many graduates in the country at the moment who cannot find jobs that match their qualifications. The capital, Thimphu, is also a good place to introduce visitors to – I’ve been visiting Bhutan for ten years, and in that period of time the capital’s population has grown from 15,000 to 150,000. Here, too, consumer society has “taken hold” of people, with the emergence of drug addiction, alcoholism and, unfortunately, to some extent, crime. Besides introducing the country, I also try to give the groups I lead the opportunity to meet my Bhutanese friends and acquaintances, because the only way to really get to know a country is to talk to the locals. So tourists who sign up for my trips can meet former prime ministers, members of parliament and archers (an important sport in Bhutan).

You give a lot of presentations about Bhutan here at home, and recently you have spoken about the country at the events of the Corvinus Mobility and Tourism Centre’s Tourism Forum series. This year the theme of the Forum is sustainability.

This is indeed a relevant and topical issue. I believe tourism can be sustainable if it is economically worthwhile and if local people can benefit, not just a narrow elite. It is important that the natural environment is not damaged, and the ecological footprint should be minimised. Tourism also changes cultures. By the way, it is precisely the sustainability of tourism that is very much in focus in Bhutan, and they want to avoid mass tourism and “overtourism”, which is what happens in, say, Venice. Tourism also has to be limited, there is a quantitative limit, and what we allow a tourist to do is also important. In this respect, Nepal has been a bad example for Bhutan with the increasing number of mountaineers who leave behind an awful lot of rubbish. It’s no coincidence that in Bhutan, climbing mountain peaks above 6000 metres is forbidden – hunting and fishing are also forbidden, as Buddhism regards and protects animals as sentient beings. I think the Tourism Forum is a very fine initiative, this is the third time I’ve come here to speak and I was very happy to do it. This forum is also a good place to listen to practitioners who know the positive and negative side of things.

I understand that tourists visiting Bhutan have to pay a USD 200 sustainability fee for every night spent in the country. That’s a pretty high amount. What is it used for?

It is a kind of tax that tourists really have to pay, which the state uses for important public purposes. These include the development of tourism infrastructure, the fostering of culture, but also education and modern and traditional health care that is free for all. Environmental protection is also a priority, for example, the country’s constitution stipulates that at least 60 percent of Bhutan’s land should be forest. The current figure is 70 percent. In fact, Bhutan wants to organise tourism on the principle of “low volume, high value”, i.e. fewer people should come who pay more and get more, so they want to develop quality tourism. In my experience, trips to Bhutan tend to be for experienced travellers over 40 who come prepared and open-minded.

What is your main goal when it comes to Bhutan?

I love showing this inspiring little country to others. My aim is also to bring Buddhist norms, values and ethics into the economy and business. It could be done, and I am convinced that it would do good to the economy, the environment and people.

Katalin Török

Cover photo: Tiger’s Nest Monastery (photo by Zoltán Valcsicsák)

More information:

Trips to Bhutan: www.bhutantour.hu

Hungary-Bhutan Friendship Society: www.bhutan.info.hu