Human values in business operations

When, approximately ten years ago, Paul Polman, then CEO of Unilever, set out to significantly reduce the company’s ecological footprint, he developed an operating model that improved not only the quality of Unilever’s products, but the working conditions of employees, too, across their global operations. We are not talking about a small company with a small profit, as Unilever’s various products are consumed by two billion people worldwide every day. Even so, Paul Polman had the courage to radically transform the operation of the company. One of his initial measures was, for example, that he abolished quarterly reports and encouraged his colleagues to think in the longer term, rather than chasing immediate returns. Thanks to the bold and ambitious transformation by Polman, Unilever’s global ecological footprint has been reduced by approximately 50% over the last ten years, while the company has performed extremely well in the stock market. According to Professor László Zsolnai, one of the editors of the collection, this case is a good example of a situation when a manager is fairly open to human-centred business practices, it pays off in the long run in terms of profit, quality, and employee satisfaction.

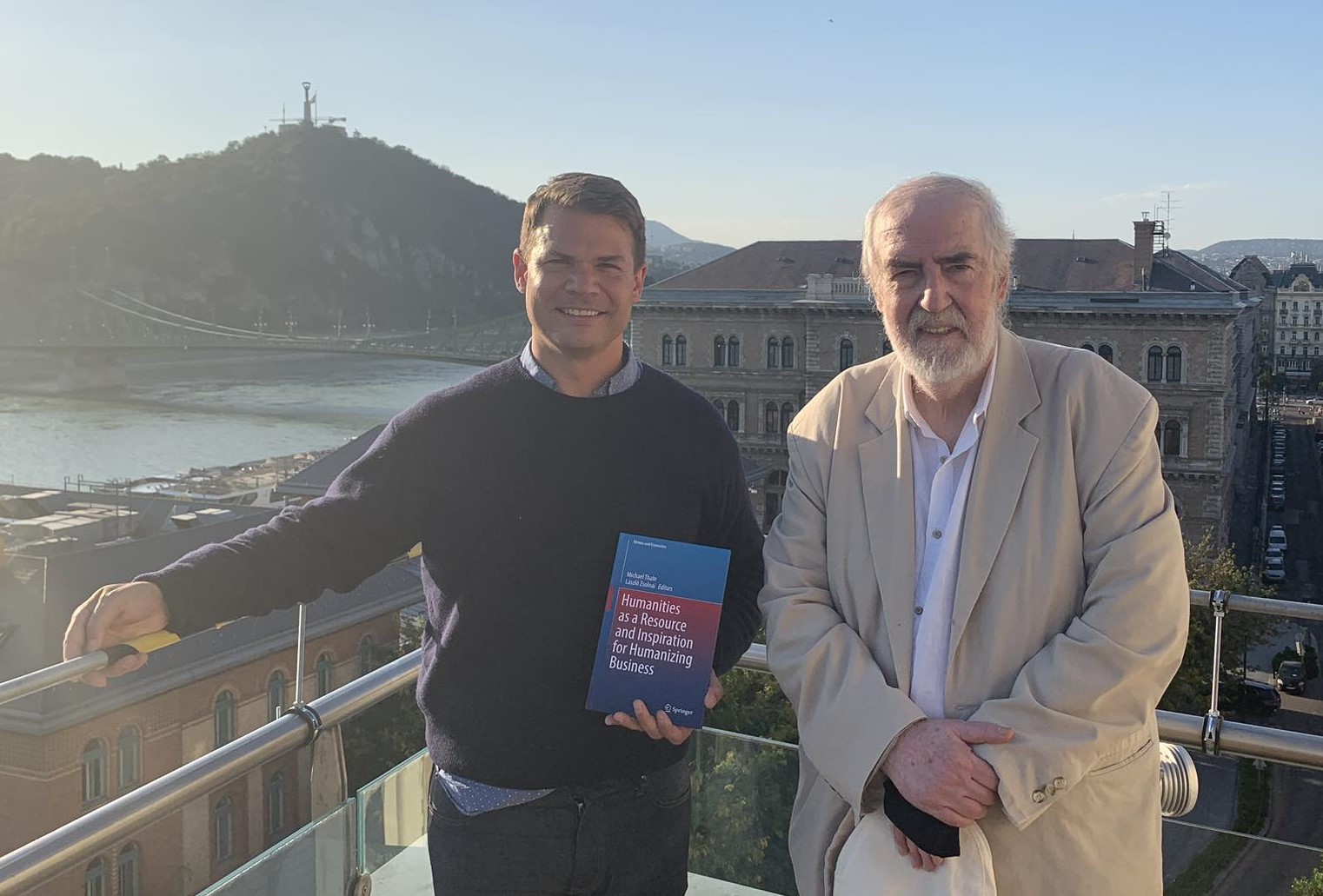

“It’s not that most managers are not open to other ways of doing business, the problem is rather the payback period. A company manager usually wants to see results within three to six months, but this kind of change in the operational model requires you to think in longer periods,” adds Michael Thate, research scholar of Princeton and co-editor of the book.

As another good example for a business approach focusing on human and social values, László Zsolnai mentions Patagonia, a California-based company that produces leisurewear mainly for young people. The company’s Buddhist leader has completely transformed the management of the company.The Patagonia Company spends enormous amounts of money on environmental and social initiatives, mainly from the extra funds that they can keep owing to the preferential taxation they enjoy because of their non-traditional company structure.

Michael Thate added that it is not only large companies where the compatibility of business operations with human values raises certain questions. Over the last decade, there have been professional debates in a number of universities around the world about how educational institutions should relate to their endowment. He mentions his own workplace: the world-famous Princeton University as an example, which has a $40 billion endowment. Thate says this raises questions of how a university’s founding model and stated values relate to the emerging financialization of the university.

The recently published collection of papers is the result of a collaboration dating back to 2017 between the Princeton University Faith and Work Initiative and Corvinus University’s Business Ethics Center. Although the lockdowns caused by the coronavirus epidemic made in-person meetings difficult, in October 2021, Michael Thate and László Zsolnai organised an international webinar series on the topic, with presentations by researchers from around the world. This is where most of the papers in the book come from.

László Zsolnai explained that the primary objective of the book is to show the various ways in which humanities and arts can help scientists, practitioners and social change agents contribute to the transformation of business and traditional management approaches.

“Humanities and arts can prove that non-financial values are vital in business and management, too, and that profit is not the only guiding principle. Business and management should use a more complex and more dynamic view of people that takes into account people’s material, psychological, and spiritual needs, and encourages both intrinsic and extrinsic human motivations,” adds the professor of Corvinus.