One million Hungarian households struggle with energy poverty

Is there a place for wood burning in the green transition, because it consumes renewable biomass, or should we fight it because it degrades air quality? Is the current energy support policy good enough? Is there energy poverty in housing estates? The conference discussed solutions to combat energy poverty by presenting the latest projects and research on 2 May at Corvinus University. According to some indicators, up to one million households – 14-18% of households –could struggle with energy poverty, while only a fraction of them are eligible for social heating or home renovation supports. Those heating with firewood are particularly vulnerable, although almost all energy users may be affected.

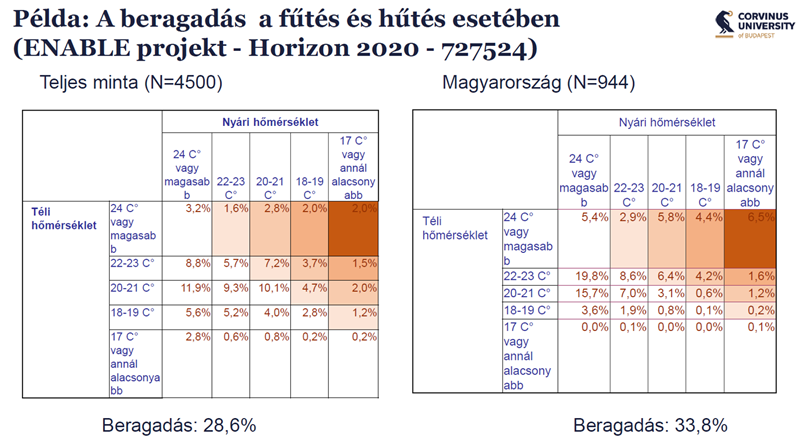

Air quality is at great risk: 720 thousand households are ready and able to burn rubbish

“The poorer someone is, the more likely they are to live in an uninsulated house or flat, spend a much higher proportion of their income on heating and have no money for efficiency investments. This is a big obstacle to the transition. Behavioural lock-in is also a hindering factor: many homes are still warmer in winter than in summer because it is fixed that the previous cheap energy was wasted,” said Gábor Harangozó, Associate Professor at Corvinus, who research the topic at the University with Mária Csutora. Harangozó said that the three main characteristics of a good energy efficiency support scheme are that the lower the income of someone, the more support they need, that there is not much administration involved in applying for it, and that it should include upfront financing. “Unfortunately, there is no energy support scheme in Hungary that meets all three professional criteria”, the lecturer added.

“There is a specific energy poverty in housing estates. For example, 13% of people living in a housing estate in Rákoskeresztúr have a much warmer home than they would like due to a lack of individual control. However, where cost allocators were installed, residents could save up to 50-70 percent of heating energy, but they had to bear the cost of renovation,” Bálint Tóth, PhD student at Corvinus, drew the lessons of a study covering 119 households in 2022 at the conference.

“Firewood is not considered a long-term and sustainable solution to replace gas for heating, even though the proportion of people using wood for heating has increased dramatically. In 2020, only 15 percent of Hungarian households heated primarily with wood, but two years later 37 percent of Hungarian households did so. Unfortunately, the average household uses dried firewood for only five months, and it would be better to use dried firewood for much longer (two years), as burning wet wood pollutes the environment and is inefficient. The government should regulate the firewood market; it would be worth introducing quality control and efficient technology,” concluded Gabriella Szajkó, Senior Research Fellow (Corvinus, Regional Centre for Energy Policy Research), in a study which was presented by Borbála Takácsné Tóth at the event. She added that the survey showed that 20 percent of respondents experience waste incineration in their environment, a third of them are not bothered by it, and 36 percent, or 720,000 Hungarian households, are technically able and willing to burn waste.

It is the poorest who are being excluded from support

“People who heat with wood are among the poorest and spend most of their income on energy compared to people who heat with gas or district heating. Hundreds of thousands of buildings should be modernised every year, including heating, but the problem is that only higher income families have access to state support due to lack of co-payments,” said Anna Bajomi, Energy Poverty Policy Officer at the European Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless (FEANTSA). She added that the Hungarian national energy and climate plan lacks information on how to reduce wood burning, which is also important because it would improve air quality. According to the expert, the use of renewable energy sources must also take into account the interests of those in need.

“Without a so-called deep renovation, it is not possible to change fuels, i.e., a comprehensive energy modernisation is needed. The positive effects of the interdependent renovation elements add up, with the replacement of windows, insulation and modernisation of the heating system all working together,” stressed Tekla Szép, Associate Professor at the University of Miskolc in her fact sheet. She said that typically low-skilled, low-income people live in energy-poor households, in small towns. Twenty to thirty thousand households are eligible for the new home renovation support scheme, while the number of renovations would need to increase to at least 100,000 per year to renew the domestic building stock in the foreseeable future. She noted that the top five income tenths benefited more from the cuts than the bottom five.

Eat or heat? – for whom sustainability is too distant a concern compared to everyday concerns

Lea Kőszeghy and Bernadett Csurgó (HUN-REN Social Science Research Centre, Institute of Sociology) discussed that there is a link between energy and food consumption, so the two problems cannot be treated separately. For poor people living in poor quality housing, the requirement for sustainability is simply an abstract concept, even if they perceive the problems.

Dóra Dudinszky, Director of Universal Services at MVM Next Energiakereskedelmi Zrt said in her contribution that gas consumption in Hungary has fallen by a quarter in two years (from 4 billion cubic metres to 3 billion cubic metres). The number of consumers below the protected band has increased from 73% to 91%. The most common way to reduce consumption is to control the heating temperature, less common is to switch to wood-burning or electric heating. Consumers also look for different ways to modernise their property, such as installing solar panels or heat pumps, insulating their homes and replacing windows.

In the closing roundtable discussion, sociologist Hanna Szemző, Managing Director of Városkutatás Kft., drew attention to the difficult situation of single elderly women and the fact that there is also energy poverty at the apartment building level. This, however, has to be managed by substantially different means than the family house. Zsuzsanna Koritár (Habitat for Humanity) spoke about that people living in energy poverty often find it difficult to access support because they are often unable to meet the administrative conditions for support (e.g., no-debt certificate issued by the National Tax and Customs Administration). Ádám Harmat (WWF) pointed out that counting firewood as renewable energy could hinder the energy transition of affected households to more sustainable sources. Integrated policy design can reduce firewood production, as opposed to promoting firewood use, even if carbon sink and conservation targets are also enhanced, in addition to energy poverty target indicators. There is also the question of the definition of what constitutes energy poverty. Many said that getting the Hungarian definition right will be key because of the obligations and rights attached to it. There are currently nine indicators of energy poverty in the academic literature – these are still being worked on by researchers – and they estimate that up to one million households in Hungary could be affected.

Photo: Edina Vári-Kiss and Borbála Takácsné Tóth