Thoughts and Words Can Be Dangerous: Banned Books, From Stencils to Samizdat

“Books have often been banned throughout history—from the Middle Ages to Ayatollah Khomeini. Thoughts and words can be dangerous, indeed. In truth, censorship doesn’t even need to be explicit—it’s often enough to make access to books difficult. And let’s not forget the possibility of self-censorship by authors or publishers,” emphasized moderator Júlia Sipos, cultural program coordinator at the Corvinus University Library, in her opening remarks.

During the discussion, one speaker recalled an incident from many decades ago: at an accounting class, when the lecturer quoted Stalin on accounting, students stood up and began chanting “Long live Stalin!” amid rhythmic applause. Between 1949 and 1953, the so-called textbooks were in fact translated Soviet party school brochures—shoddy reading, according to participants. Scholars and educators in attendance agreed that this was far from an easy period.

From Attics to Capitalist Imports

Faced with a lack of real economics textbooks, some discovered that the best source of knowledge might be the attics of former factories and banks—among old records from pre-war institutions. In one such attic search, a rat even stole a professor’s lunch. These researchers were working under extraordinary circumstances in their quest to understand how the economy truly functioned. The real breakthrough came when scholars could secure scholarships abroad, to Western Europe or the U.S., where they could spend hours immersed in university libraries—just reading and reading.

In a video interview, Hédi Huszár Ernőné, retired librarian, reminisced about the era of banned books: “By the 1970s, our university already had exchange programs—mostly with socialist countries—but the library had started buying books too,” she recalled. In the 1980s and 90s, foundations provided substantial support—up to 90,000 USD—which allowed the library to purchase foreign books and access databases. The staff regularly monitored international literature, particularly in English and German. Connections with organizations like the American Marketing Association and the international networks of Corvinus faculty members also helped improve access to quality academic resources.

Zsuzsa Nagy, retired Director General of the Corvinus University Library, recalled: “I started working in the library in 1984. From the late ’70s, the catalog already included index cards for banned works. At that time, books from so-called ‘capitalist imports’ were reviewed by subject librarians, who decided whether a title could be loaned or had to be placed in a restricted section.”

Antidotes to Mental Captivity

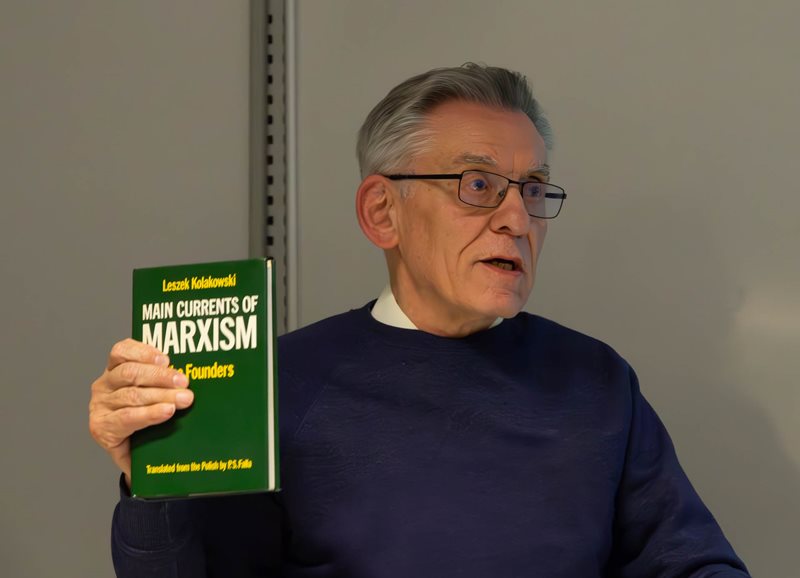

Aladár Madarász, a private professor at Corvinus University, began by introducing Hot Books in the Cold War by Alfred A. Reisch (published by CEU Press). This widely praised study tells the story of the CIA’s secret book distribution program in Eastern Europe during the Cold War, and the people behind it. Their mission was nothing less than liberating minds from ideological captivity.

Madarász also spoke about an alternative way to get banned books: you had to travel to London or Paris, where certain bookshops—part of the aforementioned program—offered three books for free and another three at half price to anyone showing an Eastern European passport. This only worked, of course, if you knew about the opportunity and dared to take advantage of it. As a later speaker mentioned, any additional books were priced well beyond what Hungarian tourists could afford.

And getting the “booty” home—books that were high-quality but banned in Hungary—was a challenge in itself. It was up to the customs officer to decide whether the books were “dangerous” and should be confiscated, or if they could pass. (Sometimes the decision hinged on the cover illustration, since the officer couldn’t always understand the title – the author’s note). Madarász shared one story where a book was taken from him at the border. He wrote to the Customs and Finance Authority demanding its return. Soon after, he was summoned to see Comrade Minister of Finance Rezső Nyers, who ultimately handed the book back.

Research Topics That Were “Not Appropriate”

Zsuzsanna Elekes, Professor Emerita at Corvinus, recalled that during her early career, poverty and Roma-related research were practically non-existent. “You simply couldn’t talk about these issues. There were no studies, even though I was working on these areas and social deviance. For decades, no academic literature on these topics entered Hungary.”

Elekes considered herself lucky to have studied under Rudolf Andorka, who strongly encouraged students to travel abroad as early as possible to access relevant resources. Together with fellow researchers, they copied and circulated important material using stencils and shared what they had in departmental libraries. “Today, this kind of information scarcity is unthinkable. I just sit down at a computer and everything is available,” she noted.

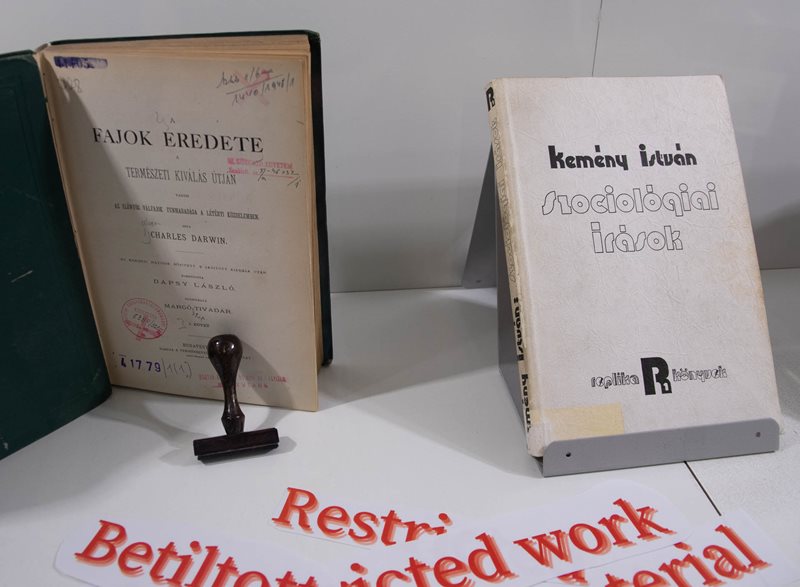

She also described the almost shocking experience of accessing sociologist István Kemény’s groundbreaking Roma research for the first time at the Parliamentary Library. Later, she met Kemény in person during a one-month research scholarship in Paris, where he handed her a copy of Magyar Füzetek (Hungarian Notebooks). Moderator Júlia Sipos added that this made perfect sense, as sociology had always been among the most system-critical disciplines.

Smuggling Books Across the Border

Zoltán Szántó, Professor at Corvinus and Dean of the CIAS research center, began his anecdote by saying he would tell a “story” from the 1980s—about a group of young men. Of course, he himself was one of them.

“Five first-year students set off on a trip across Western Europe in a borrowed Zhiguli from a local car mechanic. Since the maximum allowed foreign currency was only 70 dollars per person, they stuffed the trunk full of potatoes, carrots, and food supplies.”

Their first stop was Munich, where they visited the famous Újvári Griff Publishing bookstore. “Books there cost 60 to 80 Deutsche Marks—way beyond our means,” Szántó said. The next stop was Paris, where they found the CIA-backed bookstore. They bought as many books as they could carry. Szántó recalled one young man trying to claim a three-volume work as a “single” book to get the discount, but the cashier didn’t fall for it.

Later, they made it to London and stocked up even more. But then came the dreaded journey home—with 60 to 80 books stashed in the car. “We panicked. What would happen at the border?” They came up with a trick: after all the food was eaten, they replaced it with books and covered them with dirty socks and underwear.

“At the border, the officer demanded to check the trunk. He opened it—but the smell was so bad from all the dirty laundry, he slammed it shut without a word and waved us through,” Szántó recounted. He added that they repeated this trip for four more years, bringing home authors like Solzhenitsyn and Arthur Koestler.

“Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984?”

Péter Ákos Bod, former President of the Hungarian National Bank, professor at Corvinus University, and Doctor of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, reflected on how valuable the many personal anecdotes shared during the event were—especially for the younger students in the audience, as they offered a more vivid way to understand a bygone era.

He recalled traveling to the Soviet Union in the 1970s and then continuing on to Finland, where he inquired at a local library about Andrei A. Amalrik’s provocative book “Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984?” Naturally, the book was not available there. The librarian advised him to travel to Sweden instead, as the Swedes had published the work. As Bod noted, it was thanks to Radio Free Europe that people even knew which banned books to look for—its detailed broadcasts were a lifeline for the intellectually curious behind the Iron Curtain.

Although János Gyurgyák, historian and editor-in-chief of Osiris Publishing, could not attend the event in person, he sent a letter that was read aloud by moderator Júlia Sipos. In his message, Gyurgyák shared that his career in publishing was actually born out of the era of banned books. He went on to publish several once-prohibited or sensitive works, such as “The Truth About the Imre Nagy Case,” writings by Charles Gati, Mihály Vajda, and Oszkár Jászi’s “The Hopelessness of Communism and the Reformation of Socialism.” Among the most significant publications was Timothy Garton Ash’s “The Uses of Adversity,” a landmark analysis offering one of the first comprehensive overviews of post-regime-change transitions in the former socialist countries—including Hungary—from the perspective of a well-informed, though external, observer.

Following the talks, participants visited a small exhibition of banned books in the Corvinus University Library, which will be on display until the end of June.

Török Katalin

Photos: György Kenéz